Making games is a tough endeavour. To paraphrase a quote from Bloomberg reporter Jason Schreier’s Blood, Sweat, and Pixels tome: that any game gets made is a miracle. The bigger the game, the greater the expectations from fans and investors alike.

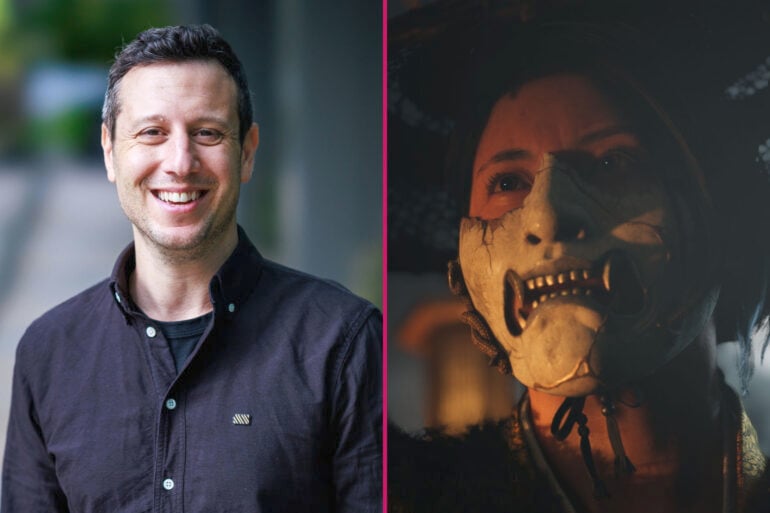

Following up the multi-million-selling Ghost of Tsushima, Sucker Punch’s PlayStation 5-exclusive sequel, Ghost of Yōtei, came with a lot riding on it. Led by a new protagonist, Atsu, played by popular actor Erika Ishii, Yōtei treads a lot of familiar ground while still aiming to make its open-world Hokkaido setting feel fresh and interesting.

In a joint interview with Sifter at PAX Aus, Rob Davis, Campaign Director at Sucker Punch — whose career began in Australia — told GadgetGuy how the studio took on the herculean task of building on a global hit.

Taking inspiration from legendary filmmaker Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Lone Wolf and Cub to create a tale of a vengeful wandering mercenary, Ghost of Yōtei represents an attempt to elevate the open world genre. But doing so was far from easy.

Space work

Open-world games have a lot of established conventions, so Davis’ greatest challenge on Yōtei was making its world feel more “handcrafted”. Hokkaido, however, with its vast expanses of land, wasn’t the easiest of settings to work with.

Big doesn’t necessarily equate to fun when it comes to games. Northern Japan is a beautiful locale, but its geography presented some challenges.

“[Hokkaido’s] giant fields are not necessarily the most intuitive start points,” Davis said. “They’re very open and in some cases they’re basins. Other ones have visual occluders like mountains, cliffsides, or a blizzard [which] naturally makes it hard to plan your route through the world.”

So players wouldn’t get lost in Yōtei’s far-ranging fields, the developers laid breadcrumbs to help organically lead the way. White flowers help Atsu’s steed run faster, but they also signpost where you’re likely to find something interesting. Similarly, in locations like Teshio Ridge, where fog limits visibility, hanging lanterns draw players in like moths to a flame, with the promise of something interesting on the other side.

“We’re always trying to find creative ways to inspire the player to investigate the world. Instead of saying, ‘Oh wow, that’s going to be a challenging space to work with,’ I think we look at it more like, ‘Well, that is what it feels like. How can we bring it to life? What ideas do we have? And what inspiration do we have?’”

Making a page-turning game

Some open-world games feel like a disparate collection of things to do. A smattering of capital-C ‘content’, if you will. Keen to create a more cohesive experience, Sucker Punch aimed to make sequences of quests that emulated the cadence of a TV series or a page-turning novel. Establishing a rhythm of dramatic upbeats and downbeats would capture player interest, encouraging them to see each storyline through.

But then a recurring challenge became how to present this narrative in a way that made for a compelling game. Game developers can only tell so much through pre-rendered cutscenes or scripted gameplay sections before starting to lose players who want to act out the samurai fantasy.

“Because there’s nothing more drab than getting a pretty rote tutorial in the game,” Davis said. “So, if we can build it into the adventure or into the character moments, clearly it’s going to make you interested in experimenting [with new gameplay features].”

He also believes that player expectations for open-world games have lifted in recent years. This inspired the design and writing teams to work harder to try and reach those expectations.

“[Players] want characters that are human and relatable,” Davis said. “And they want to feel like every part of the world contributes to the adventure and to the tone of the game.”

Bento box gaming

But what’s practically involved in bringing that adventure to life cohesively and in an engaging way? Testing. Lots of testing and iteration.

“I play the game a lot” was Davis’ self-effacing response when asked how his role as Campaign Director fit into Ghost of Yōtei’s development. Responsible for directing all of the game’s missions, he and the team would playtest Yōtei every six weeks to ensure it held up to scrutiny.

More than just playtesting for the sake of testing, there was a lot of intentionality behind each session. Another challenge with making a large open-world game was trying to appeal to a broad spectrum of players, each with their unique preferences. It wasn’t enough to serve a specific type of player; everyone should end a play session feeling satisfied, was the studio’s view.

When Davis began at Sucker Punch, Brian Fleming, one of the studio’s co-founders, outlined three different player archetypes to keep in mind when creating Ghost of Yōtei. Each one was referred to affectionately by Davis, starting with “GP Rabbits”, people who speed through the “golden path” of the game, focusing on the story. On the opposite side were the “Time Travellers”, players who take their time deeply engaging with the virtual tourism elements. Most players fit within the “Kaiseki” or “Bento Box” archetype, sampling a bit of everything on offer.

Ahead of each playtest, Davis and the team would decide which archetype they would emulate. Sometimes, that would mean going for a 100 per cent completion run or playing the one-hit kill Lethal mode. That way, they would ensure the mission structure felt cohesive, regardless of individual playstyle.

Move fast and develop things

Sucker Punch could iterate on the fly quickly, with many of its developers having worked using the same in-house development engine since 2014’s Infamous Second Son. It meant that the team could try ideas without slowing the project down.

This came in handy when working on making Hokkaido’s challenging landscapes more player-friendly. Some forests got the “weed whacking” treatment, with clearings used to telegraph what was worth taking a closer look at. One of Ghost of Yōtei’s most notable visual elements came from Sucker Punch’s speedy iteration process.

“The white flowers ended up being such a simple prototype, and they’re almost a little bit like Burnout Paradise or F-Zero,” Davis said. “There’s probably some kind of game design psychology we could work out, but you do angle towards them intuitively because you get a tiny speed boost.”

He then pointed out several tricks developers use to create player intrigue. Like how The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild is known for its use of triangles to inspire curiosity, Ghost of Yōtei employs similar techniques. Distinct landmarks, like a lone building or an odd-shaped natural structure, naturally draw the eye and make players want to find out what’s going on.

At every step, with each mission and each design element, Davis and the team leaned on two core tenets: how does it contribute to Atsu’s growth as a character, and does it evoke the feeling of being a wandering mercenary?

On the topic of bloat in open-world games, and more content for the sake of content, Davis was careful not to dismiss anything as “empty calories”.

“What is an empty calorie to some people and a heartwarming snack to others?” Davis said, in between expressing his fondness for Doritos.

But that concession didn’t mean that anything would make the cut. He stressed that the people at Sucker Punch are their own harshest critics, which was a big part of assessing whether everything in Ghost of Yōtei fit within the game’s core design goals.

“The other part of it is intuition, gut, and taste,” Davis said. “We play things a lot.”

“We look at the game. If it’s crappy, we’re fixing it or we’re getting rid of it. And our design team is pretty dang critical of their own work and of their own successes and failures. Sometimes that’s hard for us because it’s a little bit exhausting to always be looking at your work through a pretty critical lens. So, we try to be kind to one another every day.”

Designing levels from Australia to Hokkaido

Before working on Ghost of Yōtei, Davis designed levels for another of PlayStation’s flagship franchises: God of War. Getting there, however, was far from a linear path — apt for the game he ended up directing missions on.

Ever since graduating from SAE Sydney, level design has been his specialty. While his peers wanted to work on the Star Wars films being produced in Australia at the time, Davis wanted to make games.

Davis got his start working for Krome Studios on the Ty the Tasmanian Tiger series, before moving on to Destroy All Humans with the now-defunct Pandemic Studios. By his own admission, he was fresh-faced, arriving at Krome aged 21 but “looking like 15”.

In those early days, Davis tried contacting prominent game developers for advice on how to improve. One person who regularly responded was David Perry, famous for his work on 16-bit platformers like Earthworm Jim and Disney’s Aladdin.

His advice to the young Australian was to “treat yourself like an RPG character” and “level up every skill every day”. It’s advice that Davis carries to this day and likens to Sucker Punch’s approach to being “curious tinkerers”.

Despite a lot of industry uncertainty in the wake of the global financial crisis, Davis carved out a career after moving to the US. There, the closure of Pandemic Studios after launching The Saboteur led to him working on family games for a time.

Santa Monica Studio soon approached him to work on levels for the rebooted God of War series, where he would sit next to Jonathan Hawkins — who worked on the original God of War trilogy — for two years.

“[Hawkins is] truly one of the most brilliant level designers and creators a person could imagine,” Davis said. “And I realised my craft skills are fine, but the God of War team’s craft skills are like something else entirely.”

“For two years, it was almost like being in a Michelin kitchen. I learned all the tricks, and [Hawkins] was so generous with his time to teach me so many of them. It wasn’t about typing, it was about writing; a lot of us could type, but he taught me kind of how to write.”

For Davis, that remains one of the most important skills he uses when working on games. It doesn’t matter if it’s for crafting a wandering mercenary or a boomerang-wielding marsupial; the ability to create “something with a soul” and “with purpose”, as he puts it, is what helps give any art impact.

Sony Interactive Entertainment provided a code for Ghost of Yōtei on PlayStation 5 to assist with coverage.